To print yourself anew

Eric Brunner and his road from illness to new heights of artistic creativity

Most of us usually assume that everything will be fine - that things will simply work out.

Yes, from time to time some abstract worries appear, but unless there is an immediate threat, they usually concern things that are unlikely.

People fear accidents, assaults, or the outbreak of war - things over which they have little control. At the same time, they completely disregard threats that largely result from their own actions.

Alcohol abuse or the use of other intoxicating substances. Stuffing oneself with fatty, unhealthy food. A permanent lack of sleep and rest - whether due to work or pointless “entertainment”: infinite scrolling on a phone, binge-watching series on streaming platforms, or obsessive gaming.

As a result, it ends with heart attacks, hemorrhages, strokes, permanent failure of selected internal organs.

We call these lifestyle diseases.

And yes - an overwhelming majority of them can be avoided by choosing a different, healthier way of life.

Unfortunately, there are also situations over which a person has no control. Diseases that simply happen, without our influence. That could not have been avoided.

It comes suddenly. There is no appeal. A kind of sentence. A dry piece of information:

You know, statistically you have this many years left to live. Maybe a bit more, maybe a bit less. No, there’s nothing that can be done about it...

For example, multiple sclerosis. A messed-up disease. Your nervous system stops working. Normal activities become a challenge. Your body degrades from the inside. You lose mobility, you lose sensation, you lose the ability to speak.

And unfortunately - apart from the diagnosis that suddenly strikes a person like lightning - after that nothing happens suddenly anymore… It lasts. It progresses.

Some people collapse. They fall into nothingness, waiting for the end. Their emotional state erodes along with the nervous system being consumed by the disease.

But some do not. No, they don’t fight - there is nothing to fight here - they simply refuse to give up. They go on living, adapting to new conditions. They live on.

Like Eric Brunner.

Eric had been in motion his entire life - physically and creatively. And then he heard the diagnosis of a disease that systematically takes that motion away. But instead of withdrawing from life and accepting the role of a “patient,” he found a new language of action. The language of design. The language of 3D printing. The language of light.

This is a story about reclaiming agency when everything else takes it away.

Before everything began to fall apart

Eric Brunner had always been a maker. In high school, he took part in academic art programs, and after graduating he studied graphic design in his native Philadelphia, USA.

He quickly realized, however, that working on other people’s projects did not interest him. At the same time, he painted, worked with screen printing, designed posters and T-shirts for local punk rock bands. Since he didn’t have access to professional and expensive equipment and machines, he created using gear he built himself.

At some point, motorcycles appeared in his life. First as a means of transportation, then as a passion for development. Eric learned welding, metalworking, TIG welding, built and modified machines for tuning. At the same time, he raced flat track.

He worked professionally with CNC machines, programming them and machining aluminum, and after hours he returned to the garage to keep creating.

3D printing was another tool in his repertoire. A logical extension of CAD, CAM, and the “do it yourself” philosophy. He used it purely functionally, without any ideology.

He lived life to the fullest. He started a family.

Sometime around 2019, he noticed that something was wrong with his body. He started getting tired more quickly. Problems appeared with his hands - he had trouble gripping. People around him downplayed it - a doctor he asked for advice said it was exhaustion caused by the recent birth of his son and riding a motorcycle.

But that did not calm Eric. Subconsciously, he knew it was something else - something more serious. As if his subconscious was trying to tell him something.

Then came 2020 and the lockdown. Issues with health progressed. There were virtual consultations with doctors. Eventually, real EMG tests and results.

The verdict? ALS - amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. An incurable, progressive disease that takes control of the body while consciousness remains intact.

Eric emphasizes that it was a truly weird experience. Not only did he not break down - he actually felt calmer, because he finally knew what is wrong with him. Literally: “All right, I got an answer. Let’s move forward.”

After that, he took time off work, loaded up his Triumph motorcycle, and decided to take one real ride one last time. From Philly to the Grand Canyon and back. He was joined by a friend riding a Yamaha alongside him, and his wife, son, and friend's partner followed along with a RV (so they had a place to camp and rest every night).

After returning, there was complete focus on creation. First analog, then digital. Eventually, 3D printing became not only an artistic tool, but a prosthesis of independence - a way to keep designing, building, helping others, and talking about the disease in a way that is hard to ignore.

An artist who had to touch matter

Eric was never a conceptual artist in the academic sense. His art always began with the hands. With contact with material. With physical effort.

At the same time, he did not want to follow the traditional path and work in advertising agencies. Client briefs, revisions, compromises - all of that was against his nature.

I just didn't like working on other people's projects. I was much more invested in my own work.

So he created independently. He painted. He experimented. And when he needed a tool - he built it himself. Lack of money was not an obstacle. It was the driving force.

I was always very hands-on and never really had a lot of money. So whatever I wanted to do, I built it.

Before there were galleries, there were basements. Before there were art installations, there were T-shirts printed for local bands. Punk rock concerts, basement shows, dirty walls, speakers set up however they could be - as long as they played.

Eric built his own four-color screen-printing press in a basement. He printed merch for bands he knew. Not because it was a business, but because it was a community.

That culture - DIY, lack of resources, refusal to compromise - shaped him forever. It was not an aesthetic. It was an attitude.

Also motorcycles were not just a hobby for Eric. They were a language of expression.

He started with mopeds. Boring out cylinders, building exhausts, experimenting. Then Japanese motorcycles, café racers, hand-welded components. He learned TIG welding, turning, aluminum machining. At the same time, he worked professionally with CNC machines.

During the day I'm doing manufacturing… editing G-code… and at night I'm back in my garage welding and fabricating.

It was a life without pause. Work, creation, riding.

After learning about ALS, he simply decided to move forward. No hysteria, no breakdown. After returning from the trip to the Grand Canyon, Eric worked for a few more months. Then he retired.

But just formally.

In practice - he began working more intensely than ever before.

Creating as long as the hands allow

Eric made it clear: he would create for as long as his body allowed it. First painting. Then digital graphics on an iPad.

And in the background - CAD. Design. Small objects. Functional things. When he started using a cane, he designed a holder for a motorcycle.

Nobody’s going to make a cane holder for a motorcycle. So I drew one up.

That was the moment when 3D printing stopped being a curiosity, but became a tool of real innovation.

Eric designs adaptive components for other patients. A cup holder. Wheelchair parts. Simple things that the healthcare system sells for hundreds of dollars.

This is something I can make at home for 30 cents.

He started printing them and sending to others. Without a business plan. Without invoices.

Tell me what you need. I’ll print it and send it.

For many people with ALS, 3D printing sounds like science fiction. For Eric - it’s everyday life.

Illuminating ALS - light as a metaphor for the neuron

Eric searched for a long time for a form that would allow him to talk about ALS. About a disease most people do not understand - and fear.

The breakthrough came by accident - with a lithophane printed from a photo of his son.

You don’t really see the definition until the light hits it.

That sentence sparked something.

Motor neurons are like a light switch. You flip it, but the light doesn’t always come on.

This is how the monumental installation - Illuminating ALS was born. 256 portraits of people living with ALS. Printed as lithophanes. Backlit with LED lights controlled by a microcontroller.

- When the light turns on - the face comes alive.

- When it flickers - uncertainty appears.

- When it goes out - only a shadow remains.

That flickering… that’s exactly how your muscles feel with ALS.

The installation was created on a single Bambu Lab P1S 3D printer at home.

Eric Brunner created a website to ask people with ALS to submit photographs and personal stories for the project. Each portrait measures twenty centimetres diagonally, together forming a massive square structure three meters on each side.

Without illumination, the installation looks “dull and lifeless.” When the lights turn on, details and the “soul” of the portraits are revealed. The light then slowly flickers and fades, evoking the sporadic muscle twitches – fasciculations - experienced by people with ALS.

The first presentation of Illuminating ALS in took place in a large library building in Philadelphia, near the art museum. Another showing followed in a more intimate, art-focused gallery space.

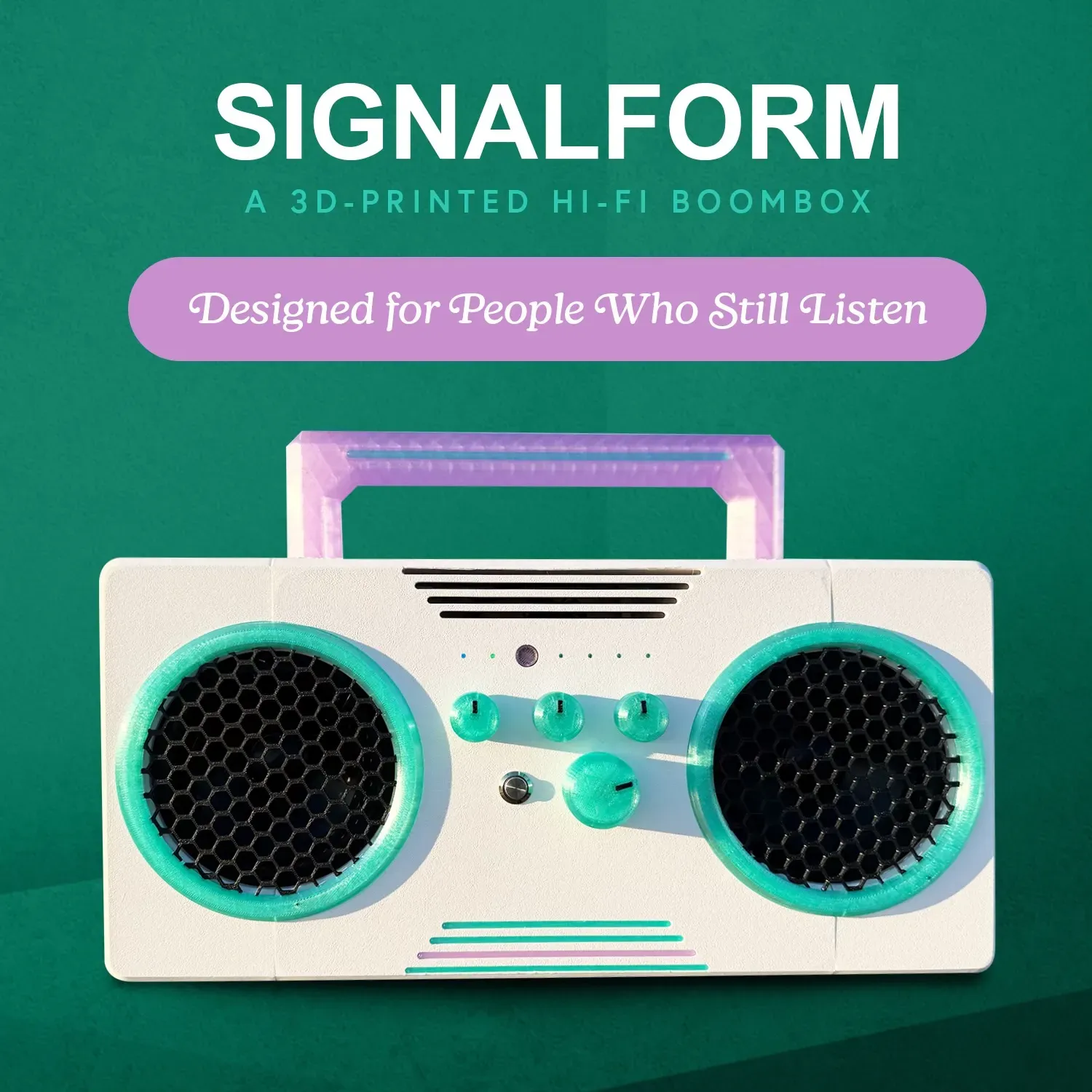

But Eric did not stop there. Once again drawing on his own life story, he decided to create another project - the SignalForm, a 3D printed boombox project.

SignalForm: Pure Hi-Fi - no apps - just sound

A youth spent in the underground music scene of Philadelphia translated into modifying audio systems and a drive to extract perfect sound from objects others considered worthless.

The real spark, however, came with the era of popular Bluetooth speakers. Eric listened to albums by his favorite bands, such as The Descendents, and noticed a gap. Portable speakers offered artificially boosted bass while losing the depth and fidelity he knew from home hi-fi systems. That became the starting point.

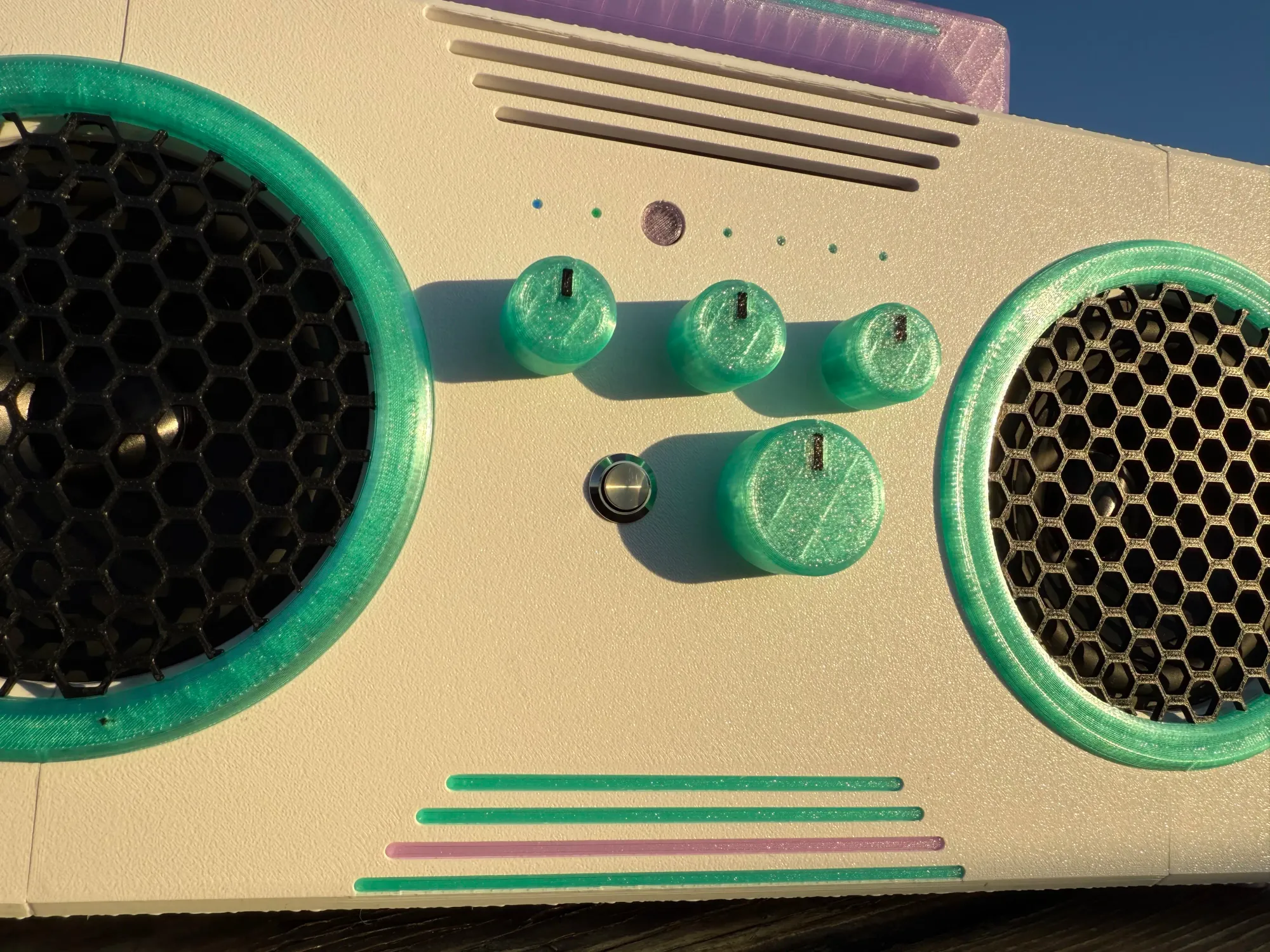

He began by disassembling a damaged JBL speaker. Then he designed and printed a new enclosure, carefully calculating the required internal volume according to the physics of vibration.

The result was astonishing: this home-built prototype sounded ten times better than the original device.

But this was only a proof of concept. The next step was to create something accessible to everyone. Eric started by developing a small, mono speaker called Afterglow, using widely available audio components. It turned out that a housing printed from ordinary PET-G could compete with traditional materials.

That led him to the main goal: creating a portable boom box radio that could be made on a standard 3D printer. He wanted to combine authentic sound with the nostalgic spirit of 1990s portable cassette players.

That's how the SignalForm Project was born - a speaker in which the left and right channels are hermetically separated, ensuring true stereo sound.

It was not just about loudness, but about fidelity - about bass that can be felt in the chest and vocals that cut through with full clarity.

Despite the progression of his disease and limited hand function, Eric was able to assemble it together with his friend, who was not an electronics specialist.

Eric meticulously documented the entire assembly process, creating detailed PDF instructions. He sees 3D printing not only as a tool for audiophiles, but as a life-changing technology.

SignalForm is now preparing for its next milestone - a crowdfunding launch on MakerWorld.

It’s a natural step for a project born from experimentation, persistence, and a belief that good design should be within reach of anyone with a 3D printer.

Creators like Eric bring more than just new products to MakerWorld. They bring stories, ingenuity, and a sense of possibility that turns the platform into something more than a marketplace — into a living, evolving community. With the support of that community, ideas like SignalForm don’t just stay concepts. They take shape, gain momentum, and become real.

Simply refuse to give up

In ALS support groups, he shares adaptive designs such as phone holders. He is shocked when people respond that a 3D printer sounds like science fiction. In response, he simply prints the needed items and sends them.

He shows therapists simple wheelchair accessories that, in medical versions, cost hundreds of dollars, while he can make them for just a few cents. His boom box - and his entire philosophy of making - is a manifesto against passivity.

Eric Brunner’s story is not about defeating ALS.

ALS is not something you defeat.

It is a story about refusing to surrender. About finding a new language of action when the old one stops working.

I design something with my limited mobility - and I can still have it physically made.

3D printing has become his extension. His hands. His voice.

Just as Eric says:

You are the limitation - not the circumstances.

All photos courtesy of Eric Brunner. All right reserved.