When 3D printing makes life livable again

How 3D printing restores dignity in everyday life, helping people move forward despite adversity

When people talk about 3D printing in medicine, they usually think of prosthetics, implants, certified medical devices, or precision surgical tools. It is a world of sterile laboratories, strict regulations, and high operating costs.

Meanwhile, another current is developing in parallel - quieter, more personal, and much closer to everyday life. This is 3D printing of non-professional, non-certified solutions that are nevertheless extraordinarily effective in supporting basic human functioning.

This is not about treating diseases or replacing healthcare systems.

It is about something simpler - and for many of us so mundane that we barely notice it: the ability to press an elevator button on your own, safely cross a doorway threshold, or go out into the rain without fearing that your trousers will be soaked again.

It is about regaining control over small fragments of reality which, when taken away by illness or a sudden accident, collectively determine whether life still feels dignified.

In this form, 3D printing is not a technology of the future. It is a technology of the present, used by people who do not wait for perfect solutions but instead reshape the world to fit themselves - layer by layer, with filament and patience.

When the technology of tomorrow reaches ordinary people

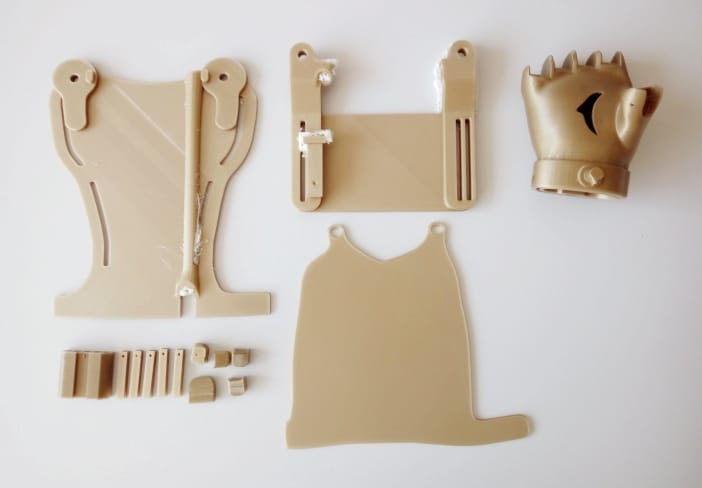

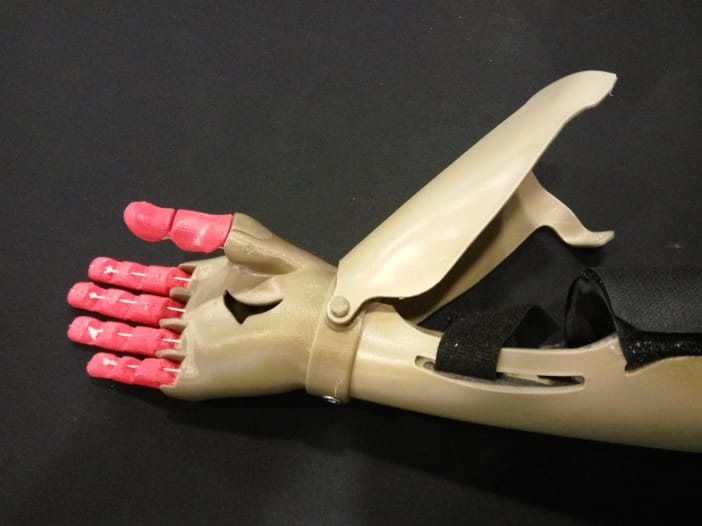

One of the best-known examples of this approach is the global e-Nable initiative. Founded in 2011 by Ivan Owen and Richard Van As, it is a distributed community of volunteers - engineers, makers, teachers, students, and hobbyists - who design and 3D print mechanical hands and arms for children and adults with limb differences, using home 3D printers.

These devices are not certified medical products, nor do they compete with professional myoelectric prostheses. Their strength lies elsewhere.

Photos: Pawel Slusarczyk archive

e-Nable hands are inexpensive, lightweight, colorful, and fully customizable. They can be scaled to fit a child’s hand, printed in different colors, decorated with superheroes or favorite animals.

For many families, this is the first time a prosthesis is not a symbol of illness, but something a child actually wants to wear.

For the volunteers themselves, the project becomes more than just printing models - it is a form of real, tangible help that requires neither large financial resources nor institutional approval.

A similar philosophy is represented by MakeGood, an organization based in New Orleans, USA. It focuses on designing assistive devices for people affected by stroke, ALS, and other disabilities.

Photos: Bambu Lab

Their most widely recognized project is a fully 3D-printed mobility trainer for young children - modular, easy to assemble, and possible to produce entirely on a Bambu Lab A1 3D printer.

In a world where specialized rehabilitation equipment can cost a fortune, projects like these demonstrate that accessibility does not always have to be a premium product. Sometimes all it takes is an open file, clear instructions, and someone willing to give their time.

The most important impact of 3D printing in these applications is not limited to improved functionality. Yes, a printed hand can help someone grasp objects, and a printed ramp can allow wheelchair access.

But just as significant is what happens on a psychological level.

People who lose physical ability due to illness, injury, or aging often lose something else as well: the feeling of being needed. Overnight, their world begins to shrink. Paradoxically, 3D printing can expand that world again - not only through finished objects, but through the very process of creating, testing, and improving.

It teaches that limitations are not an endpoint, but a starting point for new solutions.

Twan’s story: a life brought to a standstill

For Twan, life changed in an instant when an accidental fall from height caused a severe spinal cord injury in the thoracolumbar region. She lost sensation and control over the lower half of her body.

In a single moment, everything that had once been obvious - walking, working, independence - ceased to exist.

The loss of sensation and mobility below the waist pulled her into a world of frustration, limitations, and isolation familiar to many wheelchair users in cities without proper accessibility.

Moving to Kunming, in China’s Yunnan Province, was meant to be a new beginning. Unfortunatelly it quickly turned out to be just another form of confinement.

The city where she settled with her family after the accident offered independence only in theory. Muddy streets, inaccessible sidewalks, and missing infrastructure turned everyday life into an ordeal.

Days passed with her pushing the wheelchair through the city and preparing dinner. The rest of the time consisted of short rides back and forth that led nowhere.

Despite everything, she never lost her inner spark.

When a volunteer from the organization „Love Without Borders” noticed her energy and determination, she was initially unsure whether to trust yet another promise of help. Life had taught her skepticism and the need to protect her own boundaries.

Yet this meeting became a turning point, because someone saw potential in her that she herself struggled to recognize.

With that came hope - that technology could be used not only to fix technical problems, but also to rediscover meaning.

Through the organization, the idea emerged to sew compression garments for children recovering from burns. At the same time, a fundamental problem arose: how can a paralyzed person operate a sewing machine?

The solution came from occupational therapy combined with 3D printing.

Instead of forcing the body to adapt to the machine, someone decided to adapt the machine to the body. A simple, unobtrusive device was created: a 3D-printed T-shaped lever that allows the sewing machine to be activated with a gentle movement of the chin.

The first versions were imperfect. One was too heavy, another too sensitive. But 3D printing allowed for rapid, inexpensive, almost painless iterations. Eventually, a version emerged that worked perfectly.

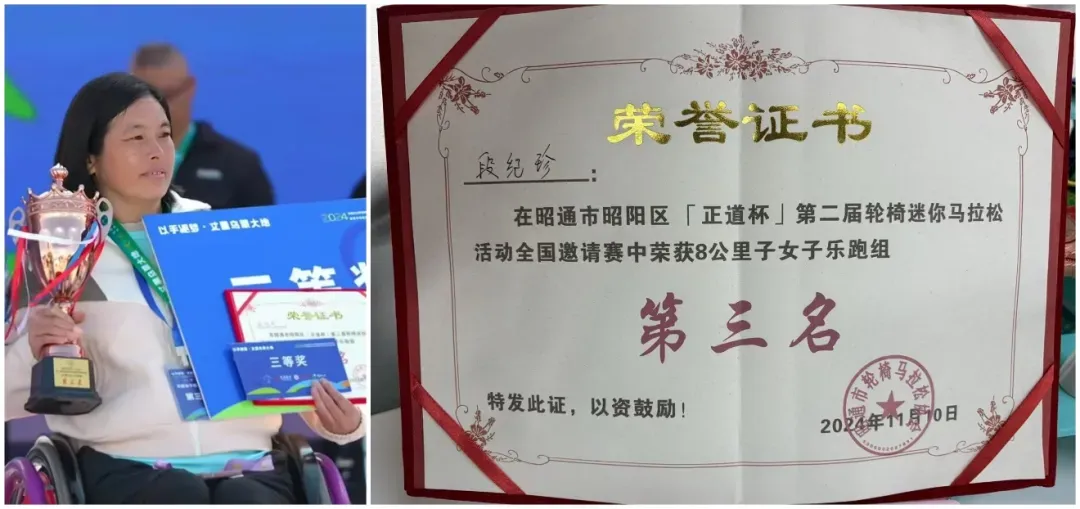

Today, Twan spends hours at the sewing machine, producing precisely fitted compression garments. On rainy days, she no longer stays home - thanks to printed fenders and a printed umbrella holder, her wheelchair can handle the weather.

She works at Love Without Borders, receives a salary and social insurance, and participates in sporting events. Most importantly, she is no longer someone who needs help - she is someone who helps others.

Uncle Wu: when subtraction turns into creation

Uncle Wu is a former chemical engineer who spent years as a professor and researcher. A rare neurological disease gradually began to take away his balance and mobility.

This steady “subtraction” of abilities - from driving, to recreational activities, to independent movement - acted like a quiet erosion of his confidence and sense of self.

After a serious fall in which he was badly injured, his son decided to transform their home into a safer, more supportive environment so that his father would not be confined to bed or wheelchair.

Although these changes increased physical comfort, the creative spirit and need for action remained dormant. Physically protected, Uncle Wu was nevertheless fading psychologically.

A 3D printer entered his life almost by accident. The first print - a small 3DBenchy boat - reawakened something that seemed long lost: the joy of making.

He quickly learned 3D modeling and began designing increasingly complex parts. Each new handle, ramp, or small gadget made his world more functional.

Today, Uncle Wu’s wheelchair resembles a mobile command center. It has holders for a tablet, lights, a fan, mirrors, and an umbrella. There is a printed tool that allows him to press elevator buttons without touching them by hand. There are ramps to overcome thresholds.

Everything is designed precisely for his needs.

Uncle Wu now prints not only for himself, but also for his family and friends - organizers, mounts, practical solutions. Companies have shown interest in his designs, but he prefers to share them freely. For him, 3D printing is not a business. It is a way of being needed.

As with Twan, 3D printing did not solve every problem. The disease did not disappear, the injury was not reversed. But something far more important changed: the sense of agency over one’s own life.

Fixing the world, layer by layer

The stories of Twan and Uncle Wu show that 3D printing in non-professional medical and assistive applications is not really about technology. It is about people.

It is about the fact that the world is not always designed for everyone - but it can be modified. Layer by layer.

If the world does not fit us, we can try to reshape it. Even if only with filament. Even if only a little.

Source: mp.weixin.qq.com